When you hear a song that just clicks, that moves you, or gets stuck in your head, there's a powerful, often unseen force at play: Understanding Chord Progressions. These aren't just random sequences of notes; they're the very backbone of musical storytelling, the harmonic journey that guides a listener's emotions and expectations. Think of them as the grammar of music, allowing composers to build narratives, create tension, and deliver satisfying resolutions.

For anyone who wants to write music, produce tracks, or simply deepen their appreciation for the songs they love, grasping chord progressions is fundamental. It's how you unlock the secrets behind every hit song, every classic rock anthem, and every poignant film score. This guide will take you from the basic building blocks of chords to crafting your own compelling musical narratives, transforming you from a passive listener into an active participant in the language of music.

At a Glance: Your Quick Chord Progression Toolkit

- What They Are: Predictable patterns of two or more chords that form the emotional and structural foundation of a song.

- Roman Numerals: The universal notation for chords (I, IV, V for major; i, iv, v for minor; vii° for diminished).

- Chord Building: Chords are constructed from specific scale degrees (e.g., a Major triad uses the 1st, 3rd, and 5th notes of a major scale).

- Functional Categories: Chords serve roles like Tonic (home base), Dominant (tension), and Predominant (leading to tension).

- Common Progressions: Familiar patterns like I-IV-V-I and I-V-vi-IV appear across countless genres.

- Crafting Your Own: Start with a key, use the tonic, experiment with common patterns, and always trust your ear.

- Beyond Basics: Explore 7th chords, polychords, and modulation for richer harmonic landscapes.

What Are Chord Progressions, Really? The Narrative Behind the Notes

At its heart, a chord progression is a sequence of two or more chords played in succession. But it’s more than just a list; it’s a journey. Imagine the chords as characters in a story: some are stable and comforting, others are full of anticipation, and some create intense drama. The progression is the plot, guiding these characters through a series of interactions that evoke a specific emotional response.

Individual chords are like single words – a collection of pitches that sound good when played together. A progression, however, is a sentence, a paragraph, or even an entire chapter. It's what allows a melody to soar, a rhythm to groove, and a song's emotional core to resonate deeply with its audience. Without chord progressions, music would largely lack its sense of direction, its capacity for tension and release, and its profound ability to tell a story without words.

The Language of Roman Numerals: Your Musical GPS

Before diving into specific progressions, you need to understand how musicians universally label chords within a key. We use Roman numerals, and they're far more intuitive than they might seem.

Here's the breakdown:

- Capital Roman Numerals (I, IV, V): These indicate major chords.

- Lowercase Roman Numerals (i, iv, v): These signify minor chords.

- Lowercase with a Degree Symbol (vii°): This denotes a diminished chord.

This system is brilliant because it's universal. A I-IV-V progression sounds the same harmonically whether you play it in C Major (C-F-G) or G Major (G-C-D). The actual notes change, but the relationship between the chords remains identical, making it easy to transpose and analyze music across different keys. Most progressions typically consist of three to five chords, though shorter or longer sequences are certainly possible.

Building Blocks: How Chords Come to Be

To truly understand chord progressions, you need a basic grasp of how individual chords are constructed. Chords are formed from specific notes within a particular musical key or scale.

The Major Scale: Your Foundation

Every chord progression starts with a scale. The major scale is the most common foundation, built on a universal formula of whole steps (W) and half steps (H). A whole step is two semitones (like moving two frets on a guitar or two piano keys, including black keys), and a half step is one semitone (one fret/one piano key).

The major scale formula is: W – W – H – W – W – W – H

Let's use C Major as our example, as it has no sharps or flats, making it easy to visualize on a piano:

| Scale Degree | Note (C Major) | Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1st (I) | C | Tonic |

| 2nd (ii) | D | Supertonic |

| 3rd (iii) | E | Mediant |

| 4th (IV) | F | Subdominant |

| 5th (V) | G | Dominant |

| 6th (vi) | A | Submediant |

| 7th (vii°) | B | Leading Tone |

| From these scale degrees, we can build different types of chords. |

Essential Chord Types and Their Formulas

Most common chords are triads, meaning they consist of three notes.

- Major Triad: Built from the 1st (root), 3rd, and 5th scale degrees of its major scale.

- Example: C Major (C-E-G). This chord typically sounds bright, happy, or stable.

- Minor Triad: Built from the 1st (root), flattened 3rd (minor third), and 5th scale degrees of its major scale. Alternatively, it's the 1st, 3rd, and 5th of its minor scale.

- Example: A Minor (A-C-E). This chord often evokes a sense of melancholy, introspection, or seriousness.

- Diminished Triad: Constructed from the 1st (root), flattened 3rd, and flattened 5th scale degrees.

- Example: C Diminished (C-Eb-Gb). Diminished chords create significant tension and are often used as passing chords to resolve to a more stable chord.

- Seventh Chords: These add a fourth note—the 7th scale degree—to a basic triad, enriching its sound and often increasing its harmonic complexity or tension.

- Example: C Major 7th (CMaj7) = C-E-G-B. This adds a sophisticated, mellow quality. Other common types include Dominant 7th (V7) and Minor 7th (m7).

- Chord Inversions: An inversion means playing the same notes of a chord, but with a different note in the bass. For example, a C Major chord (C-E-G) can be inverted to E-G-C (first inversion) or G-C-E (second inversion). Inversions change the perceived "weight" of the chord and can smooth out basslines in a progression.

The Role Call: Functional Categories of Chords

Chords within a progression aren't just decorative; they serve distinct functions that drive the musical narrative. Understanding these functions is key to crafting compelling progressions.

- Tonic (I, iii, vi): This is your home base. The tonic chord (I) feels like resolution, rest, and stability. Think of it as the beginning and end of a musical sentence. Other chords like the mediant (iii) and submediant (vi) are closely related to the tonic and can offer variation while still feeling somewhat settled.

- Dominant (V, vii°): This is where the tension builds. The dominant chord (V) strongly pulls towards the tonic, creating an anticipation of resolution. The leading tone chord (vii° - diminished) also creates intense tension, often acting as a substitute for the dominant due to its shared notes and strong pull to the tonic.

- Predominant / Subdominant (IV, ii): These chords act as a bridge, moving away from the tonic but not yet creating the strong pull of the dominant. The subdominant (IV) and supertonic (ii) chords often lead into dominant chords, setting up that feeling of impending resolution.

Most satisfying progressions follow a functional flow: Tonic → Predominant → Dominant → Tonic. This creates a natural ebb and flow of stability, departure, tension, and return.

Journey Through Harmony: Types of Progressions

Chord progressions can be categorized based on the scale they draw from, each offering a unique flavor.

- Diatonic Progressions: These are the most common, using only chords derived from a single major or natural minor scale. They sound coherent and "right" because all the chords belong together harmonically.

- Example (C Major): C – G – Am – F (I – V – vi – IV). This is a textbook diatonic progression.

- Natural Minor Progressions: These use chords built exclusively from the natural minor scale, which typically sounds melancholic or somber.

- Example (A Minor): Am – G – C – F (i – VII – III – VI).

- Melodic Minor Progressions: Built from the melodic minor scale, which raises the 6th and 7th degrees when ascending (to create a stronger leading tone to the tonic) and lowers them when descending (to sound more like natural minor). This adds a sophisticated, often jazz-like quality.

- Example (C Minor): Cm – F – G – Cm (i – IV – V – i), but with the F and G chords potentially deriving from the raised 6th and 7th of the melodic minor, giving them a major quality.

- Harmonic Minor Progressions: These use chords derived from the harmonic minor scale, which raises only the 7th scale degree to create a strong leading tone back to the tonic. This often results in a distinct, exotic sound, particularly with the V chord becoming major and the vii° chord appearing frequently.

- Example (A Minor): Am – F – G#dim (i – VI – vii°). The G#dim chord is a clear indicator of harmonic minor.

The Greatest Hits: Common Chord Progressions You Need to Know

Some chord progressions are so effective, so universally pleasing, that they've been used in countless songs across genres and generations. Learning these is like learning common phrases in a new language—they give you an immediate toolkit for communication.

- I–IV–V–I: The bedrock of rock and roll, blues, and folk music. It's incredibly sturdy and satisfying.

- Feel: Strong, grounded, triumphant.

- Examples: "Wild Thing," "La Bamba," and even the verse of "Despacito" uses this in various keys. In Bb Major, it would be Bb-Eb-F-Bb.

- I–V–vi–IV: Arguably the most popular progression in modern pop music, often dubbed the "Axis of Awesome" progression. It's catchy, emotionally versatile, and incredibly adaptable.

- Feel: Hopeful, bittersweet, reflective.

- Examples: "Let It Be" (The Beatles), "Don't Stop Believin'" (Journey), "She Will Be Loved" (Maroon 5). In C Major, this is C-G-Am-F.

- I–V–iv–I: This progression, while less ubiquitous than the I-V-vi-IV, still offers a distinct flavor, especially with the minor subdominant (iv).

- Feel: Can be reflective, slightly dramatic, or even nostalgic.

- Example: Portions of Toto's "Africa" hint at this kind of movement, though often with variations. If played in C Major, this would be C-G-Fm-C. The

Fm(iv) adds a touch of wistfulness often unexpected in a major key.

- vi–IV–I–V: This is simply an inversion or a different starting point for the I-V-vi-IV, but starting on the minor

vichord gives it an immediate melancholic or contemplative feel from the outset.

- Feel: Emotional, introspective, longing.

- Example: The verse of "Let It Be" starts with Am-G-C-F (vi-V-I-IV, a slight variation, but captures the essence).

- I–vi–ii–V: A classic "doo-wop" progression, also known as the "Rhythm Changes" progression in jazz, particularly the first four bars. It's been used for centuries and has a timeless appeal, often sounding sophisticated.

- Feel: Smooth, jazzy, classic, romantic.

- Example: "Heart and Soul," "Blue Moon." In C Major, this is C-Am-Dm-G.

Genre Spotlight: Progressions with a Twist

Different musical genres often develop their own signature harmonic patterns. Learning these can help you compose authentically within a style or consciously break its conventions.

- Jazz: The II-V-I (two-five-one) is the absolute cornerstone of jazz harmony. It's a fundamental movement that establishes a key and allows for rich improvisation.

- Example (C Major): Dm7 – G7 – Cmaj7. Jazz musicians frequently add chord extensions (9ths, 11ths, 13ths) and substitutions to this basic framework.

- Another vital jazz progression is the "turnaround" I-vi-ii-V, which cycles elegantly and provides a harmonic anchor for improvisers.

- Example (C Major): Cmaj7 – Am7 – Dm7 – G7.

- Blues: The 12-bar blues is a specific, iconic chord progression that defines the genre. It’s a rhythmic and harmonic pattern based almost entirely on the I, IV, and V chords.

- Example (in the key of E):

- E7 (I) - E7 (I) - E7 (I) - E7 (I)

- A7 (IV) - A7 (IV) - E7 (I) - E7 (I)

- B7 (V) - A7 (IV) - E7 (I) - B7 (V)

This creates a compelling cycle of call and response, tension and resolution, that is instantly recognizable.

Your Turn: Crafting Your Own Chord Progressions

Now that you understand the building blocks and common patterns, it's time to put theory into practice. Writing your own chord progressions is one of the most rewarding aspects of making music.

1. Choose Your Key & Mood

This is your starting point. Do you want something bright and uplifting? Go for a major key (e.g., C Major, G Major). If you're aiming for something more somber, mysterious, or introspective, a minor key (e.g., A Minor, E Minor) is a better choice. Don't overthink it; just pick one to begin.

2. Start Strong with the Tonic

Most progressions begin and end on the tonic (I or i) chord. It establishes your home key and provides a sense of arrival. A typical progression might involve three to five chords to create a satisfying phrase. While simple triads are a great start, consider adding 7th notes to your chords later for added depth and color.

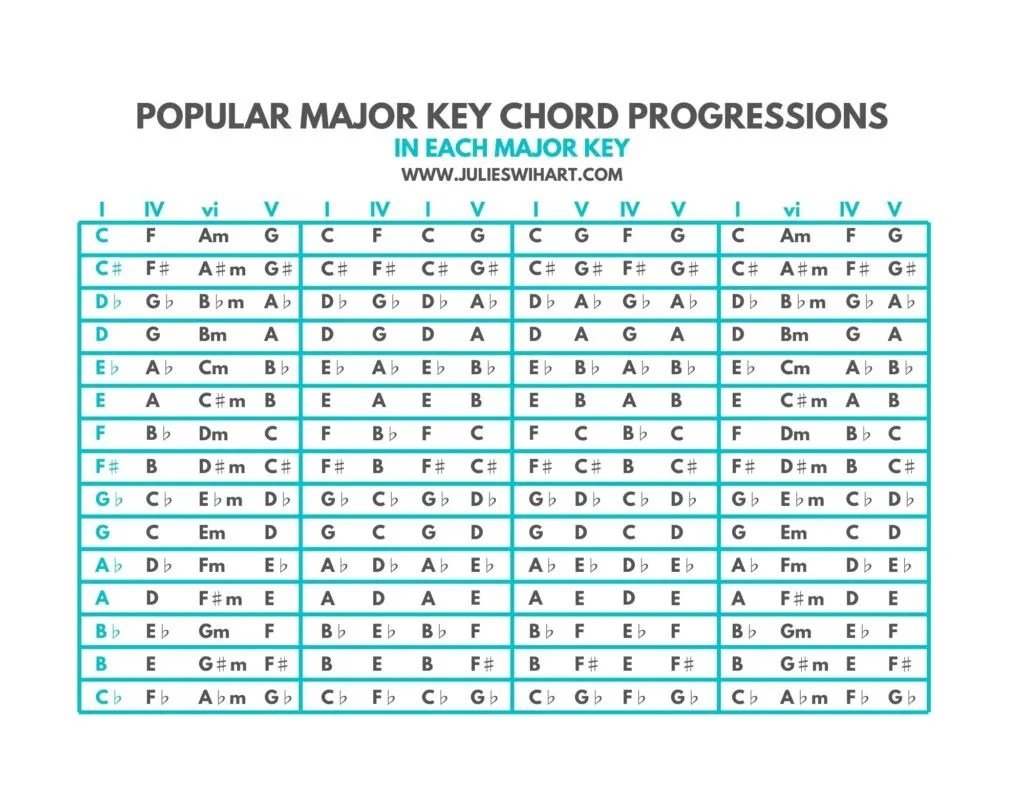

3. Use Charts as Your Map

Once you've chosen your key, look up the diatonic chords available in that key. Many online resources and music theory books provide "chord charts" that list all the major, minor, and diminished chords for any given scale. These charts are invaluable for seeing the relationships between chords and identifying common patterns. Don't be afraid to borrow ideas from the "Greatest Hits" progressions listed above and adapt them to your chosen key.

4. Add Flavor with Extensions & Transitions

After you have a basic sequence, you can refine it.

- 7th Chords: Swap a major or minor triad for its 7th chord (e.g., C major to Cmaj7, or D minor to Dm7). This instantly adds sophistication.

- Passing Notes/Chords: Think about inserting single notes or quick chords between your main progression chords to create smoother transitions. These don't always have to be diatonic, but use your ear to guide you.

- Inversions: Experiment with chord inversions to create more interesting bass lines or to keep the upper voices of your chords moving smoothly.

5. Listen and Experiment: The Most Important Step

Music isn't math; it's art. The "rules" of theory are guides, not unbreakable laws. Once you've laid out a progression, listen to it. Does it evoke the emotion you intended? Does it flow well? Try moving chords around, substituting a major for a minor (or vice versa if diatonic), or adding different extensions. Your ears are your ultimate judge. Don't be afraid to try "wrong" chords; sometimes, the most unexpected choices lead to the most interesting results.

Beyond the Basics: Tips for More Engaging Progressions

Once you're comfortable with basic diatonic progressions, you can begin to explore techniques that add complexity, surprise, and a unique personality to your music.

- The 4/3 & 3/4 Chord Tricks (Triads Simplified):

- Major Chord (4/3): To build any major triad from its root, simply go up 4 semitones to find the second note, then up another 3 semitones to find the third note. (Example: C + 4 semitones = E; E + 3 semitones = G. Voilà, C Major!).

- Minor Chord (3/4): For a minor triad, reverse the order: root + 3 semitones + 4 semitones. (Example: C + 3 semitones = Eb; Eb + 4 semitones = G. That's C Minor!). These quick tricks let you build chords rapidly in any key.

- Unleash the Dominant 7th (V7): This is perhaps the most powerful chord for creating direction. A dominant 7th chord (V7) is a major triad with a flattened 7th (one semitone lower than the major 7th). For example, a C Major 7th is C-E-G-B, but a C7 (dominant 7th) is C-E-G-Bb. The tritone interval within the dominant 7th creates a strong desire to resolve down a fifth to the tonic. It's incredibly common in blues, rock, and jazz for its forward-driving energy.

- Exploring Polychords: For a truly rich and complex sound, try polychords. This involves stacking two distinct major or minor chords on top of each other to form a single, larger chord. For example, if you combine a C Major triad (C-E-G) with a G Major triad (G-B-D), you get a Cmaj9 chord (C-E-G-B-D). Polychords can add a unique harmonic density and sophisticated texture, often heard in jazz and contemporary classical music.

- Expanding Your Harmonic Palette: Don't limit yourself to purely diatonic progressions forever.

- Modulation: Introduce chords that temporarily shift the key. This adds excitement and takes the listener on a longer journey before returning home.

- Borrowed Chords: Use chords from the parallel minor key in a major key song (or vice versa). For instance, in C Major, borrowing an Ab Major chord (from C minor) can create a wonderfully dramatic or melancholic moment.

- Chromaticism: Incorporate notes and chords that are outside the current key for brief, expressive moments. This is where your ear becomes your most crucial guide.

To truly understand how these elements fit together and to quickly prototype new ideas, consider utilizing tools like our chord progressions generator. It can help you visualize and hear different combinations, providing a powerful sandbox for your musical exploration.

Mastering the Language: Your Next Steps

Understanding chord progressions is more than just knowing a few common patterns; it's about gaining fluency in the emotional language of music. It empowers you to analyze your favorite songs, deconstruct their appeal, and then apply those insights to your own creative work.

The journey doesn't end here. Continually do the following:

- Analyze Songs: Every time you hear a song you love, try to identify its progression. Many online resources provide chord charts for popular songs, allowing you to see the Roman numerals in action.

- Practice: Play through common progressions on your instrument. Feel how they resolve, how they create tension, and the emotions they evoke.

- Experiment: Dedicate time to simply playing around with different chord sequences. Don't aim for a finished song; just explore the sounds and connections.

- Listen Actively: Pay attention to how different genres use progressions. Notice the subtle shifts, the unexpected turns, and the satisfying resolutions.

By actively engaging with chord progressions, you're not just learning music theory; you're learning to speak music. And once you can speak it, you can tell your own unique stories, move your own listeners, and truly master the expressive power of sound.